“Tribal lifestyle is threatened by development”

January 23rd, 2018 A simple gift of hospitality prompted Mridul Upadhyay, 26, a Commonwealth Correspondent from New Delhi in India, to consider how small minorities are affected by the pressures of global demand and development.

A simple gift of hospitality prompted Mridul Upadhyay, 26, a Commonwealth Correspondent from New Delhi in India, to consider how small minorities are affected by the pressures of global demand and development.

What was the best thing offered to you to eat, as a gesture of hospitality, when you visited someone’s home? For me it was clove, a spice, offered by an old tribal woman in an Indian rural village.

Maybe it was one of the costliest or most special things available in the house to offer, or it’s their culture to offer such things to the guests. But as I learned later, it was not grown or collected, rather purchased by family.

The East India company brought clove from its native home in Indonesia to the Company’s spices gardens in India in 1800 AD. How, then, did offering it become a part of a tribal family’s mode of hospitality?

In this village, the people settled when displaced during construction of a big dam two decades ago. Currently, some 70 families have made their huts, kuccha houses and farms here. They eventually got power connections, but fetching water is still a big issue. Now, because of construction of a highway and some cement factories, the land price has increased here. So the administration, maybe in pressure from businessmen or maybe acting in anticipation of more development, is trying to displace them again. It is not letting these tribal people stay on this land, as these people don’t hold the property rights to the land.

These people, once landowners, got money when their lands were supposed to be submerged in the water of the dam. People spent most of it in transporting whatever they had. For some, there was no guidance on what to do with so much money and no help in reinvestment. Soon they lost the money and land both.

Demand and supply based globalisation has also had negative effect on these minorities by affecting their choices to grow, eat and get things in market. Previously, they used to grow and have a seven to eight grain meal, but now they are growing, getting and eating rice and wheat-based staple food mostly, which has led many families to malnutrition.

India has over 105 million tribal people, which constitute nearly nine per cent of India’s total population. Tribal people were the native inhabitants of the land in India, before Aryans settled approximately 5000 years ago and sent tribal people to deep jungles. Their culture, religion, tradition and food are still very different.

Aryans brought their religion, and while making Indian constitution in 1949, tribal people were subsumed in the Hindu religion. Previous social interaction with Hindu religion had diffused the caste system among the tribal people and constitutional process increased such forced interaction. Tribal people had been living in small groups with their local governance and rules, so there is no political unity for them to challenge strong national parties. They also faced discrimination that put them in low caste Hindu category.

Tribal peoples read in secular government run schools, are sometimes taught communist philosophy in workshops, are approached by Christian missionaries – and then at home they are tribal. They are confused about what religion or philosophy to follow. They are never trained in keeping their own culture alive, which is perfect in their own imperfections. They are forgetting their rituals, festivals, traditional food and practices and following the majority around them.

In the constitution, India gave freedom of worship and following religion, but what if the minority is getting influenced by majority religion and culture, in an environment that offers them no cultural protection? It might not sound like atrocity crimes or genocide, but it’s a slow, systematic and unnoticed death of diverse cultures.

These are the poorest of the poor and the most marginalised of the marginalised. Can one answer if they ask why and whom to vote in elections? Who cares for such minorities of just 70 families in those rural villages? What are we doing in the name of globalisation, development, economy, super power, consumerism and personal comfort? Are the developed not developing by crushing not just the dreams but also the lives of the so-called undeveloped? Have we really set our priorities perfectly and thoughtfully?

Overwhelmed by all these thoughts, I kept that clove in the pocket of my shirt, close to my heart.

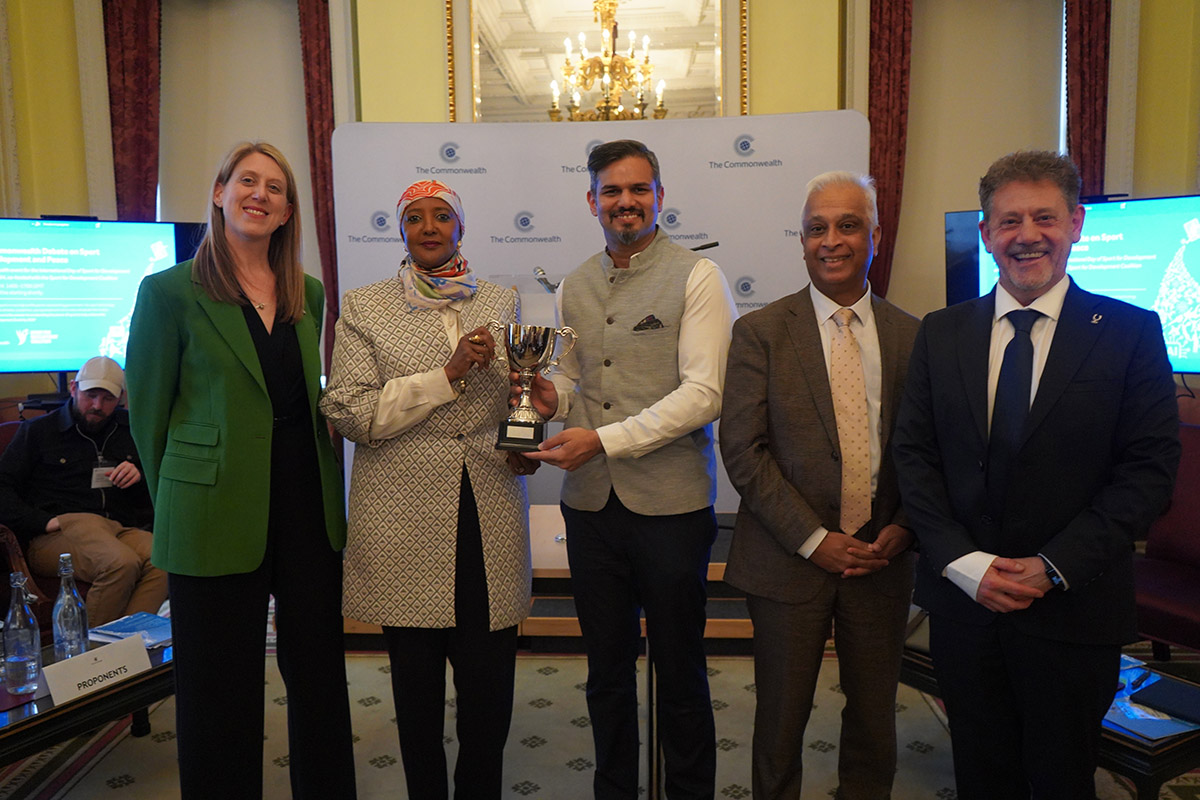

Photograph credits: Suresh Singh, Ekta Parishad

………………………………………………………………………………………

About me: I am a development professional who is very passionate about peacebuilding, transformational leadership, organisation building and writing. I have been working on Sustainable Development Goals at the community, national and international levels through ground projects, activism, training and policy advocacy for last 10 years. Currently, I am the Asia Coordinator for UNOY Peacebuilders and chief advisor for Youth for Peace International. I aspire to share the insight, shift and experience that I gain through my diverse interactions.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Commonwealth Youth Programme. Articles are published in a spirit of dialogue, respect and understanding. If you disagree, why not submit a response?

To learn more about becoming a Commonwealth Correspondent please visit: http://www.yourcommonwealth.org/submit-articles/

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………