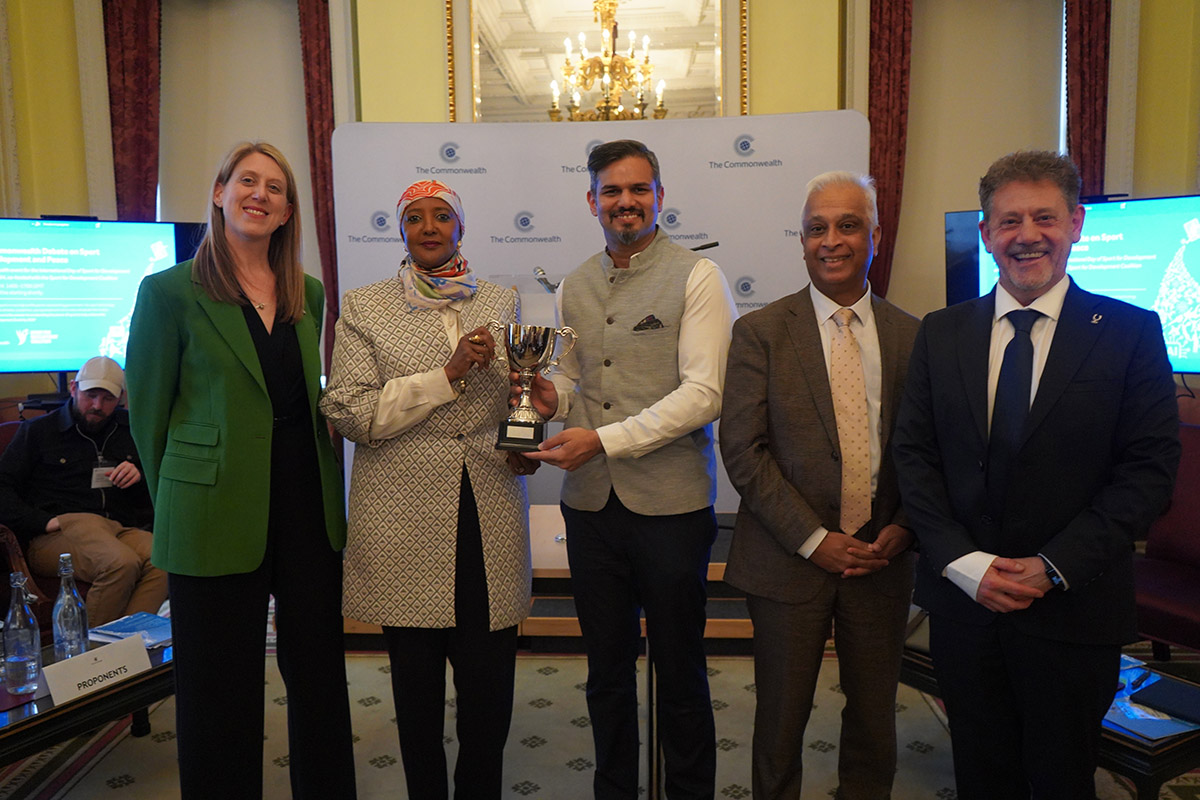

“Girls Rising: perspectives from Sri Lanka”

June 29th, 2015 Salma Yusuf, a Sri Lankan-based human rights lawyer, lecturer and Commonwealth Correspondent, was invited to present a Sri Lankan perspective following the Colombo screening of the documentary “Girls Rising: Education of Girls”.

Salma Yusuf, a Sri Lankan-based human rights lawyer, lecturer and Commonwealth Correspondent, was invited to present a Sri Lankan perspective following the Colombo screening of the documentary “Girls Rising: Education of Girls”.

The right to education has been recognized since the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights (UDHR) in 1948, which states in Article 26 that the UDHR proclaims that everyone has the right to education. It highlights this right as being universal and not open to discrimination based upon factors among which are gender, ethnicity and religion.

The right was further enshrined in a range of international conventions including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. More recently, the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Millennium Development Goals also underline gender equality in attaining goals including education. However, it must be remembered that though the right to education is universally recognized, its interpretation varies substantially in a national context, that is, the mode of securing this right varies with location. In some countries, the right is enforceable through national legislation while in others, it has a persuasive effect in the making of public policies.

While there is no place for complacency in the present situation, we have every reason for hope because discrimination is not in principle or policy against women and girls, but rather in practice which is also not directly discriminatory.

Sri Lanka introduced free education for all children from primary to university level in 1945. It has been argued that in the case of Sri Lanka, women have been beneficiaries of this policy. The law made it compulsory for a child to gain a school education in Sri Lanka, and went one step further to cast a duty on all parents of a child not less than five years old and not more than fourteen years old to enable such a child to receive an education.

Moreover, in Article 27 (2) of the Constitution of Sri Lanka, the state is pledged to the complete eradication of illiteracy and assurance to all persons of the right to universal and equal access to education at all levels.

It is positive reality to live in a country where laws, policies and principles are not directly discriminatory against girls and more importantly, girls are not culturally and socially stigmatized.

The importance of educating girls cannot be overstated. It is said that when you educate a man, you educate an individual but when you educate a woman, you educate a family and a generation. Moreover, empowering women through education has important implications for women’s economic empowerment, women’s access to information, knowledge and skills and access to decent and remunerative work. Viewed in a wider sense, education enhances women’s capability to make choices, develops self-confidence, decision-making power and autonomy.

The challenges that Sri Lanka faces in this subject are several. The content of education is gendered; it reproduces stereotypes through teaching methods and textbooks. Further, it is found that young women tend to enroll in courses such as cosmetology, sewing and cookery that do not train them for formal employment. Women who choose ‘non-traditional’ courses face difficulties finding training, apprenticeships and employment. The disparities in the provision of education facilities and services and socio-economic constraints in urban settlements, remote villages, plantations and conflict-affected areas have resulted in pockets of educational deprivation.

In contrast to gender parity in general education, there are notable imbalances in intakes of female students to the engineering and technology-related courses in universities, as well as technical colleges. This gender imbalance in enrollment to courses in science and technology can also be traced to the impact of traditional gender role stereotypes prevailing in the family and society in Sri Lanka.

Undoubtedly, one of the social groups that has benefited most from the revolutionary educational reforms implemented is women. The figures tell the story: in 1946, when overall literacy rate for the country was 57.8 per cent, only 43.8 per cent of the female population was literate as opposed to 70.1 per cent of the male population. By 2001, however, the percentage of literate women had gone up to 90 per cent of the female population in comparison with the 93 per cent of the male population. How did the gap between male and female literacy come to be narrowed so rapidly and significantly during the intervening 60-odd year period? The answer is ‘free education.’

The enlightened policy of ‘free health’ was another revolutionary welfare policy measure that went hand in hand with ‘free education’, bringing about a remarkable improvement in Sri Lankan women’s physical quality of life. There was a time when Sri Lanka was touted as the ‘poster child’ in UN development circles for this reason. As women live longer, parents become more willing to invest in their education. This is within the underlying rationale that human beings tend to prioritize their struggles, and when health and education are competing claims, the former is the winner. Therefore, in the case of Sri Lanka, when free health was provided, education became an option for consideration.

The question then that begs an answer is how did ‘free education’ benefit women in particular? As long as education is not free, parents with limited resources must make a choice regarding whom to educate and how much. Given the deep-rooted gender norms in Sri Lankan society, it would seem logical for parents to expend their limited resources on educating their sons. This is the economic rationale that has been addressed when it comes to educating women in Sri Lanka.

The cultural rationale still persists, but in a progressivelly lesser degree, in Sri Lankan society. For long years, ‘education’ was seen as ‘spoiling’ women for marriage and hence less desirable, so parents prefer to save funds for dowry rather than invest in education of their daughters.

It is only through more girls being educated that societal attitudes toward women can be challenged and translated to positive gender roles in communities and cultures.

photo credit: Pencils via photopin (license)

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

About me: I am a Human Rights Lawyer based in Sri Lanka, and a visiting lecturer in law at University of Northumbria – Regional Campus for Sri Lanka & Maldives, and previously at the University of Colombo.

I serve on both national and international programmes in the fields of law, governance, human rights and transitional justice. I hope to build on my work in policy development, research, advocacy and publishing going forward.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Commonwealth Youth Programme. Articles are published in a spirit of dialogue, respect and understanding. If you disagree, why not submit a response?

To learn more about becoming a Commonwealth Correspondent please visit: http://www.yourcommonwealth.org/submit-articles/commonwealthcorrespondents/

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………