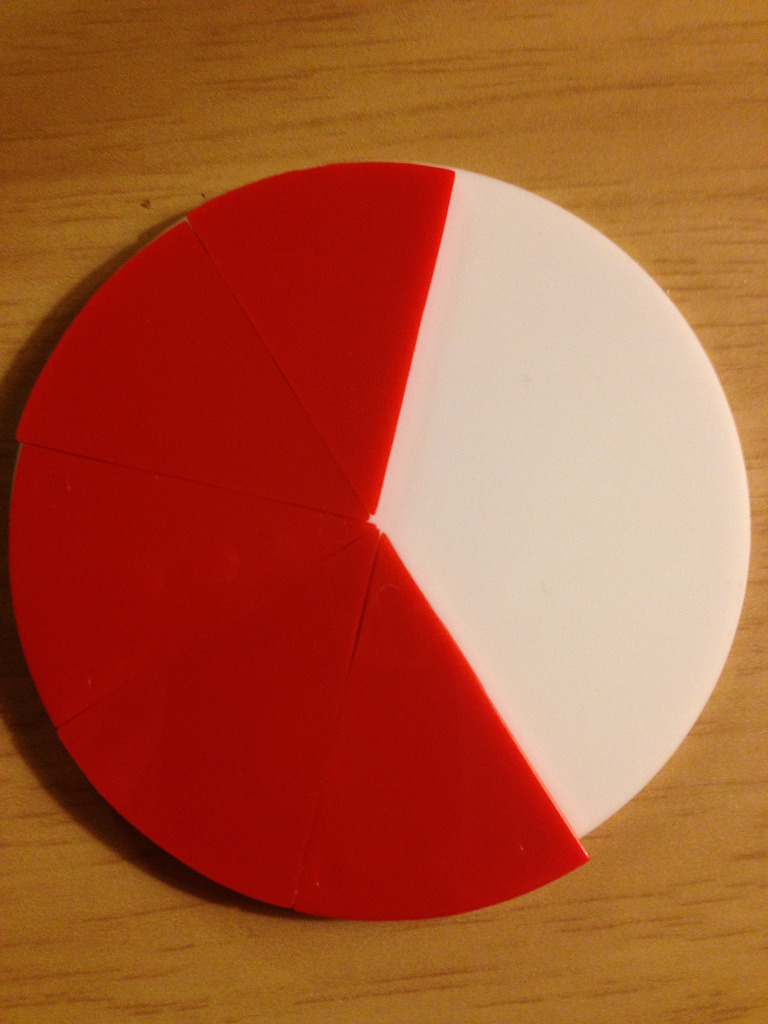

“Two-thirds rule and yet no gender equity”

April 25th, 2017 Seven years after the promulgation of a new, all-inclusive Constitution in 2010, Kenyan women’s journey to full institutional and de jure equality remains a daunting mission, writes Aisha Anne Habiba, 27, a Correspondent from Mombasa in Kenya, as she looks at what she describes as the convoluted quagmire of gender equality.

Seven years after the promulgation of a new, all-inclusive Constitution in 2010, Kenyan women’s journey to full institutional and de jure equality remains a daunting mission, writes Aisha Anne Habiba, 27, a Correspondent from Mombasa in Kenya, as she looks at what she describes as the convoluted quagmire of gender equality.

Women still have little to no bargaining power as there are a myriad factors that hinder their representation in decision-making processes, mainly due to unequal distribution of resource allocation and the weak correlation between policy initiatives and their implementation. The Two-Third Gender Principle highlights this apposite issue.

To put this into perspective, the constitution of Kenya endorses the rights of women and men as equal by law and therefore entitled to equal opportunities in political, social and economic spheres. It specifically states that “not more than two thirds of members of elective public bodies shall be of the same gender”. Another clause further reiterates that “the State shall take legislative and other measures, including affirmative action programmes and policies designed to redress any disadvantage suffered by individuals or groups because of past discrimination”.

Insofar as the 33/67 per cent rule is considered unequivocal in constitutional terms, it is yet to be translated into a definite realisation. In December, 2012, the Supreme Court ruled that gender equity as an affirmative action was “progressive in nature” and gave Parliament up to August 2015 to execute the ordinance. Almost two years down the line, consensus is yet to be reached on an appropriate framework of enactment. The Kenyan Parliament and the Attorney General have clearly abjured their constitutional mandate, which has denied women and marginalised persons their constitutional provisions under an inegalitarian informed rhetoric locking them out of decision-making posts.

Women’s participation in political office is entrenched in the Sustainable Development Goals adopted by several UN member states to end poverty, promote sustainability and the development agenda. However, political representation of Kenyan women is dismal, if not unsavoury, compared to other East African countries. In the 2013 General Elections, no single woman was elected for gubernatorial or senatorial positions; the Senate, National Assembly, and Cabinet governing bodies responsible for setting precedent have also failed to observe the minimum threshold.

Amendment Bill Number 4 of the Constitution enunciates that membership of the Senate and National Assembly adhere to the two-thirds gender principle. Egalitarian doctrines as espoused in the Constitution maintain that equality of opportunity in the political arena and public office is a fundamental human right. Barring women from political posts has affected the passing of Bill of Rights aimed at empowering women, as male-dominated political systems are not benevolent enough to ensure that women’s bargaining power receives enough empirical attention. Realisation of the two-thirds statute has proven to be a convoluted quagmire at best, as the Bill of Rights can only be revised through a popular referendum. However, the proposed Bill could not be passed due to a lack of quorum as several Members of the Parliament boycotted the vote.

In recent developments, the Kenya High Court seems to have reached a new milepost in advancing women’s rights. It will exercise its jurisdiction to dissolve Parliament if it fails to enact the legislation within the stated timeline ahead of the August general elections.

However, achieving gender parity will take more than “technical solutions” like dissolution of Parliament; it will require cross-sectoral and multidimensional efforts in order to uphold the rights conferred on women. A proper framework to enforce compliance must be set in place; political parties must embrace a policy of inclusion to end systemic institutional marginalisation of women; come up with a proper framework to enforce compliance with the two-thirds gender principle, and promote women’s civic education in politics through capacity building.

The prospect of an unconstitutional Parliament and a revolutionary constitutional crisis is already looming ahead.

Photo credit: Kimberly_Herbert via photopin (license)

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

About me: Working as a Gender, Communications and Research Assistant at an NGO, my passion is to inspire positive and sustainable breakthrough in the livelihoods of vulnerable women and children dealing with diminished status. I am ardent about the eradication of poverty caused by gender inequality because I believe that poverty is sexist. My ultimate goal is to be the next Wangari Maathai, an activist-writer who would pioneer a women’s movement aimed at lobbying for improved socioeconomic rights for women.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Commonwealth Youth Programme. Articles are published in a spirit of dialogue, respect and understanding. If you disagree, why not submit a response?

To learn more about becoming a Commonwealth Correspondent please visit: http://www.yourcommonwealth.org/submit-articles/

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………