“Bangladesh has solution for access to justice”

October 18th, 2016 Mahdy Hassan, 24, a Correspondent from Dhaka in Bangladesh, looks at an initiative in Bangladesh aimed at easing courtroom backlogs and delays that can hamper access to justice. He argues that Alternative Dispute Resolution brings justice in a variety of cases, and should be widely incorporated in the legal system.

Mahdy Hassan, 24, a Correspondent from Dhaka in Bangladesh, looks at an initiative in Bangladesh aimed at easing courtroom backlogs and delays that can hamper access to justice. He argues that Alternative Dispute Resolution brings justice in a variety of cases, and should be widely incorporated in the legal system.

The Judiciary of Bangladesh is deadlocked in a vicious cycle of backlogs and delays in criminal cases and civil suits, which is alarming for ensuring access to justice, rule of law and the human rights of marginalised and underprivileged communities.

The Bangladesh Law Commission reports more than 2.6 million cases pending in district courts.[1] To overcome these challenges, the Law and Justice Division is implementing “Justice Sector Facility (JSF)”[2], a $5.5 million USD project with technical and financial support from the UK’s Department For International Development and the United Nations Development Progrmme (UNDP) Bangladesh.

The direct beneficiaries are the key justice sector institutions, victims/complainants, accused persons, relatives and friends of victims and the accused, convicts, prisoners: vulnerable, poor, excluded and people from marginalised communities, children, and women’s groups. JSF has built a strategic partnership with National Legal Aid Services Organisation (NLASO) to introduce Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) in the formal justice system as a way to revamp legal aid services across Bangladesh.

A significant feature of Alternative Dispute Resolution is appointment of a Judicial Officer as ‘Mediator’ to provide legal advice as well as conduct resolution for both pre- and post-trial cases. Legislation enacted in 2014 has opened up this opportunity to reduce time and minimise the cost of justice significantly. This initiative is available to all people of Bangladesh, who can apply to District Legal Aid Offices’ Alternative Dispute Resolution. Most recently, ADR has been officially included for the first time as a referral mechanism to ensure dispensation of quality and timely justice.

In 2016, the most significant improvement of Alternative Dispute Resolution in Bangladesh is to incorporate District Legal Aid Offices as mediators. As a result, courts of laws are now sending civil suits for mediation to the district offices. The Justice Sector Facility project provided support to amend the Legal Aid Services Act in 2013 and incorporate ADR, including it as a legal aid service and authorising legal aid officers as mediators in civil cases, providing training, guidelines and orientation for lawyers and other stakeholders.

Tracking from January to June 2016 shows a total of 699 applications for ADR, and that 77 per cent of the total applications have already been finalised. In addition, USD $150,155 was recovered and handed over directly to the poor litigants through ADR in civil and family matters. During 2015, a total number of 705 applications were registered for ADR and 74 per cent of the total applications were finalised successfully.

The National Legal Aid Services Organisation (NLASO) has organised 128 awareness meetings on ADR across the country as of August, 2016, not only to orient lawyers but also to inspire other justice sector stakeholders. Furthermore, a recent study named “Global Survey on Legal Aid; Bangladesh Case Study” conducted by UNDP Bangladesh revealed that respondents, when asked what types of cases were formerly received legal aid, said 35 per cent were related to family suits, 19 per cent were related to money suits, 31 per cent were related to land disputes and 15 per cent were criminal cases. The results indicate that the maximum number of legal aid cases can be mitigated through ADR process.

To minimise case backlog utilising the ADR mechanism, some more steps should be taken immediately, such as development of an ADR guideline for District Legal Aid offices, policies on government and NGO collaboration to promote ADR, improved capacity of the district legal aid office not only to conduct ADR but also on fact finding and to introduce a strong follow up mechanism for post ADR cases. Also required is advocacy with both Supreme Court and Ministry of Law and Parliamentary Affairs for appointing 64 District Legal Aid offices, to establish a network with other NGOs who have huge experience on ADR, revision of the legal aid lawyers’ code of conduct to incorporate a provision for supporting dispute resolution, and review of other legislation to insert ADR provision. This includes land survey tribunals related rules, policy regulations regarding money recovery suits and to improvement of NLASO’s capacity to make district legal aid office as the ADR corner.

I confidently recommend that other countries that are facing the challenges of case backlogs that hinder access to justice can also start the Alternative Dispute Resolution practice within their respective legal systems.

[1] “Additional Report and Recommendations to reduce case backlog” Report No 138 of Bangladesh Law Commission; viewed from <http://www.lc.gov.bd/reports/138.pdf> accessed on 27 September 2016

[2]See for the project details: <http://www.bd.undp.org/content/bangladesh/en/home/operations/projects/democratic_governance/justice-sector-facility.html> accessed on 27 September 2016

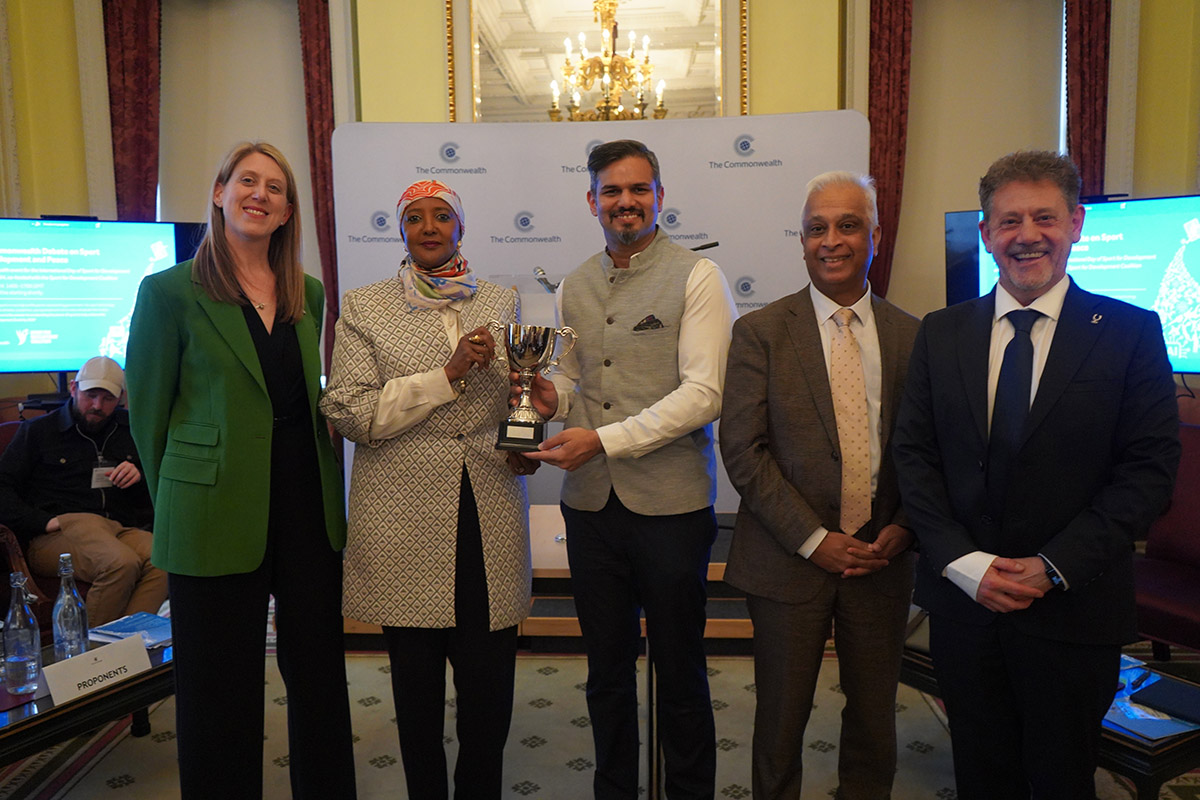

Photo credit: courtesy of NLASO

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

About me: Currently, I am working with Relief International, Bangladesh Country Office as TIP Program Associate to assist in implementing U.S. Department of State TIP Office funded project. In addition, I am working as a member of Commonwealth Youth Human Rights and Democracy Network (CYHRDN).

I completed my LL.B. and LL.M. degree from University of Dhaka. I love to write and to conduct research on different human rights and development issues and aspects. I dream a world without hunger, poverty and exploitation.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Commonwealth Youth Programme. Articles are published in a spirit of dialogue, respect and understanding. If you disagree, why not submit a response?

To learn more about becoming a Commonwealth Correspondent please visit: http://www.yourcommonwealth.org/submit-articles/

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………